Losses and Light: A Guided Prayer for All Saints Sunday

Before any of us were anything at all, we were God’s.

Read MoreBefore any of us were anything at all, we were God’s.

Read MoreYou know, I’m always saying that Jesus asks us to do difficult things, because to me, it feels like he is. I mean, when I read Jesus’ teachings, I feel like this Play-Doh. I don’t know what shape I’m supposed to be. I don’t know what I’m for.

But, luckily for all of us, Jesus doesn’t start his teaching today with me. He starts with God.

Read MoreThey must think this question is so tempting to Jesus. After all, they’ve seen that he can draw a crowd. They saw how upset he was over the money changers in the Temple. Asking a question about money? This is a sure bet for getting Jesus to lose his cool, slip up, and get caught by Rome. Then, Rome takes care of this Jesus problem for them.

Read MoreMore than that, I think the words of this psalm hold wisdom for us as we all navigate our mental health, especially when we go through periods of stress. I know we like to think of ourselves as more educated than our ancestors, and that may be true some of the time, but I also know that we as humans have been dealing with our mental health before we knew to call it that, and that our ancestors do have hard-won wisdom to share with us, if only we look for it.

Read MoreA sermon for Sunday, September 27, 2020, based on Psalm 78 and Philippians 2.

Would you pray with me? God who loves us more than we can ever know, thank you for bringing us to this time and this place. By your spirit, make your presence known here today. And may the words of my mouth and the meditations of all our hearts be acceptable to you, our Rock and our Redeemer. Amen.

Do you remember those WWJD bracelets that people used to have? Or maybe not the bracelets, maybe that wasn't the fad here, but do you remember the bumper stickers and bookmarks and posters? WWJD was a big thing in my formative years as a Christian. We were always told to ask ourselves, whenever we weren't sure what to do, what would Jesus do?

Because, as you all know, no matter how many Sundays we spend in church or how many bible studies we go to or how often we pray, there will always be something in this world that confuses us. There will always be some situation where we're not sure what to do or how to respond. We can be sure about many things as Christians: the unending love of God for us, the need we all have for forgiveness, the importance of the Bible, and the importance of loving our neighbors. But even though we know these things for sure, we're always being faced with new situations. Like those word problems in math class, we're always having to figure out how to apply what we know to be true.

Which is why I love our two passages this morning and I love the fact that the lectionary pairs them together. The psalmist asks God to listen to them and to witness how they are continuing to teach God's words and love to the generations. Paul, in Philippians, does much the same, but centered around Christ. The psalmist brings answers to old riddles. Paul brings Christ's example to answer the questions that the Philippians are living with. Across the centuries, we see God shedding light on our questions.

So what light does God have to shed on our lives today and how might we carry that knowledge with us into our weeks? Well, let's start by looking at the psalm.

I'm fascinated by the phrase, “riddles from days long gone” in the CEB translation of the psalm. It’s “dark sayings” in other translations, and when I put those two phrases together, I know exactly what it means, but I have such difficulty putting words to it. I think, though, that the rest of the psalm gives us the clue that we need to understand it. The psalmist is telling the story of all the things that God did for Israel when Israel came out of the land of Egypt and wandered in the wilderness before coming into the promised Land. I can imagine how mysterious God’s wonders must have seemed to those who came out of Egypt. Mysterious and powerful. Too much for us to fathom, too much for us to understand, in the same way that the night sky is full of riddles, dark and mysterious and wonderful and powerful. We will tell the generation how awesome God is, the psalmist is saying, awesome in that deep and powerful way that God is awesome.

And here's where the light comes in. Here's where the love comes in. This awesome God, who could choose to burn up the whole world in that fiery pillar, instead chooses to give freedom and abundant Life to all. God, this awesome God, who does not need to listen to the cries of the Israelites in Egypt or in the wilderness, instead chooses to hear them and lead them into freedom and provide for them abundant streams of flowing water. This awesome God, who could choose to start all over again on some other planets somewhere far away, chooses to hear us when we complain and when we grumble, because God knows that our complaints and our grumbling come out of needs deep within our hearts and souls. God knows us inside and out and God loves us completely and so God chooses to be generous with us, no matter what our situation, but especially in times of need.

This is the first answer to our questions that we can carry with us throughout this week. We are loved by an awesome God and so, no matter what the week ahead brings, we know that we will be provided for abundantly.

That's actually key to understanding what Paul tells us in Philippians. I think that this passage from Philippians, what's known as the Philippians hymn, could be another one of those riddles or dark sayings, if it weren't for the love and light of God. Let's turn to Philippians let's see what we have to learn here.

Paul asks us to have the same mind that Jesus had, which in itself seems to be a very mysterious saying, but Paul goes on to explain. The mind that Jesus had was a mind that put service first. Jesus, being with God and God from the beginning, could have, like God in the fiery pillar, chosen to come to Earth in the form of an emperor or a king, forcing us to do exactly as he says. But that's not what he does. In fact, Jesus does not want to do that. he does not consider equality with God something to be coveted. Jesus, who could have summoned all of the power in the universe to bend it to his own will, chose instead to become a servant. Not only a servant, but a servant who expects nothing in return for his work.

It is this selflessness, this selflessness that didn't fight back even on the cross, that makes Jesus worthy of elevating above all. Jesus was able to give everything he had, keeping nothing back, and through that giving, we have all been saved and set free. This is what Jesus did. This is what Jesus does. This is what God's love will always do.

Jesus's selflessness is possible only because of who we know God to be, who the psalmist attests that God is. We know that God has the ability and the willingness to give us whatever we need, to provide for us no matter what we're going through. We never have to worry that we will be abandoned. We never have to worry that we will be alone. We never have to worry that we won't have enough. If God can provide streams of flowing water in the desert, God can provide what we need. And when we trust that God will always be with us and will always give us what we need, then we can give without holding back. Then we can have the mind of Christ, who served others until the very end.

That's the other answer that will shed light on our lives this week. Because we are loved with the everlasting love of an awesome God, we can offer ourselves as servants of others without losing anything at all. Anytime the spirit moves us to say a kind word to someone else, to have a difficult conversation in order to repair a relationship, to offer an act of kindness to someone, to be there for someone going through their own time of difficulty and darkness, to reach out and listen to someone who has a story that needs to be told, or just to smile with our eyes above our masks as we go about our days, we know that we can do all of these things and more because we are held in the love of God who will never let us go. We can serve others in this world boldly, without fear, and without holding anything back. We can see the world as Jesus sees it: beautiful and precious and worth saving.

That's how we have the mind of Christ. That's what Paul means when he says for us to work out our own salvation with fear and trembling. Paul means for us to ask ourselves, in every situation, what would Jesus do? How can I serve others in this situation, the way Jesus would?

The beautiful thing for each of you is that you already know the answers to those questions. You have spent your lives wrapped up in the love of God. You know how to trust God with all that you have and all that you are. And you know how to serve.

So be encouraged, friends. No matter what the world throws at you, no matter what the situation is, you know what Jesus would do and you know how to do it. You just got to keep on doing it.

Amen.

A sermon for Sunday, September 20th, based on Exodus 16:2-15 and Philippians 1:21-30.

Would you pray with me?

God, we are tired. God, we are worn. God, we are ready for your kingdom to be here and now. Be with us in this time and this place. And may the words of my mouth and the meditations of all our hearts be acceptable to you, our Rock and our Redeemer. Amen.

After a long spring and an even longer summer, fall is almost here, and I couldn’t be more thankful. I’m so ready for this little bit of normal, this promised and faithful change in the weather, to come into this world that has been so abnormal for these past six months. COVID has tired me out and I’m ready for a break.

Our passage this morning is a gift from the lectionary, a break from our time with the teachings of Jesus. We’re taking this break because we need it, because even though Jesus does tell us to come unto him, for his burden is easy and his yoke is light, I, in my infinite wisdom, did not put that particular passage into this sermon series, and I feel that we need a brief spot of comfort today.

So this morning, we join the Israelites in the wilderness. They have come out of Egypt, through the freeing work of the Lord, crossed the Red Sea, and now they find themselves hungry and wandering, unsure of where to go next, two and a half months after leaving Egypt. They, too, are tired, exhausted, even, living in an uncertain present with an even more uncertain future. The people are at their breaking point, and so they say to Moses, in verse 3, “ If only we had died by the hand of the Lord in the land of Egypt, when we sat by the fleshpots and ate our fill of bread; for you have brought us out into this wilderness to kill this whole assembly with hunger.”

“Sure,” the Israelites say, “Sure, we were enslaved in Egypt, and Pharaoh murdered our sons and kept us in captivity, but at least there was bread! At least there was soup with meat in it! What good is freedom if we’re just going to starve? Freedom doesn’t feed us.”

Now, we might look at them with pity, and maybe a little bit of sass. These are the people who God led out of Egypt! These are the people who saw the plagues, who lived through the first Passover, who walked through the Red Sea on dry land, who have been led by a pillar of cloud and fire. These people have seen God’s wonders, have experienced God’s saving grace firsthand, and only two and a half months later, they’re complaining because they don’t have enough meat in their diet? Have they forgotten who God is?

But let me tell you something. When you’ve spent every day of your life struggling to keep it, you don’t exactly have the space to notice when your hunger is clouding your judgement. When every moment is spent in survival mode, quiet moments of self-analysis are hard to come by. When you have spent generations longing for freedom, there is a necessary period of adjustment, because if the world around you was built on your oppression, it isn’t going to welcome your freedom. Freedom is the first, but not the only step, on the way to abundant life, and freedom does not feed us.

Praise be to God, though, that God hears our cries, even when our leaders, just as tired as we ourselves are, treat our complaints with contempt. Manna, a pure gift from God, bread enough for the Israelites to eat their fill, falls from the sky. They fled from Egypt without waiting for their bread to rise, doing what they had to do to escape into freedom, and as soon as they ask for it, the bread of the wilderness is given to them for their sojourn. And quail as well, a gracious gift of protein for bodies long overworked and under-cared for.

Friends, our bodies are overworked and they need care and my guess is that our spirits are much the same. We have lived in the struggle that the Apostle Paul speaks about. We have been striving to live our lives in a manner worthy of the gospel of Christ, striving to live into our best understanding of the good news of our Lord Jesus. I can’t speak to the condition of your spirit, because that is something only you and God truly know, but speaking for myself, I find I am caught in the same conundrum as Paul. I am hard pressed between the two: my desire is to depart and be with Christ, for that is far better; but there is so much left to do here, in this place, that to remain is more necessary. How I long for the coming reign of God, when the good harvest is done and the rest can begin! How I long for the fullness of peace, the presence of justice and grace, to be here and now! How I long for the day when Jesus makes all things right!

And yet, I know, there is manna in the wilderness. Though we are weary, God will give us strength for today and bright hope for tomorrow. Though we are burdened, it is for freedom that Christ has set us free. Though there is still a long road ahead of us before we finally arrive in the promised land, a road that will require strength and dedication and creativity, we do not walk it alone. God hears us. God hears us. And God is always more ready to hear than we are to pray, more ready to give than we are prepared to receive. God is always with us, even in this season of tiredness, and more than that, God is ready and waiting to revive us. All we have to do is ask.

We’re tired, yes. Living is hard right now, yes, and for many, it’s been hard for a long, long time. But thanks be to God for the promise of a better life for all, for rest for our weary selves. Take the time to rest, because you need it. Always be ready to rest, because God calls us to it. Take the time to ask God to give you what you need for the days ahead, because God is ready to give it. But more than anything else, do all that you can to prepare yourselves for the road ahead. We’ve still got a ways to go.

Amen.

A sermon for Sunday, September 13, 2020, based on Matthew 9:9-17.

Would you pray with me?

God our Healer, who is making all things new, thank you for bringing us to this time and this place. By your Spirit, make your presence known here today. And may the words of my mouth and the meditations of all our hearts be acceptable to you, our Rock and our Redeemer. Amen.

Have y’all ever picked out life verses, those verses of scripture that speak to you and have been with you all your life? It was a big thing when I was in high school and in college. I remember memorizing verses, writing them on index cards and taping them to my mirror, making collages out of them. And these verses, they were always something like Jeremiah 29:11: “For I know the plans I have for you, declares the Lord, plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you a hope and a future” or Philippians 4:13: “I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me,” or Psalm 46:10: “Be still and know that I am God,” or Romans 12:2: “Do not be conformed to this world but be transformed by the renewing of your minds, so that you may discern what is the will of God—what is good and acceptable and perfect.”

And you know, Jesus has something like life verses in the gospel of Matthew. I mean, we see him quoting from the Jewish scriptures during his temptation and during the Sermon on the Mount, but there’s only a few times that he quotes scripture as is, without offering a reinterpretation, without out saying, “You have heard it said, …but I say to you…” One of these few scriptures that Jesus quotes with full approval, one of his life verses, if you will, is the one we hear him quote in our passage this morning, Hosea 6:6: “I desire mercy, not sacrifice.” He actually quotes it twice in Matthew, both here and in Matthew 12. “I desire mercy, not sacrifice” is clearly important to Jesus.

Now, I know it’s not a competition, but oof. Jesus’ life verse really blows mine out of the water. I mean, Jeremiah 29:11 is nice and all, but it’s plucked out of the context of Jeremiah, a brief moment of light in the middle of the misery that Jeremiah and his people are going through, and it’s meant to apply to a nation, not to a person. Hosea 6:6, on the other hand, is a key verse in Hosea, a core part of the prophet’s teachings. Hosea, like most prophets, is preaching to Israel, asking them to turn back to God before destruction comes, because Israel has been putting its trust in foreign leaders and in going through the motions of faith, which has led to destruction and hurt felt most often by the vulnerable people in Israel. Hosea 6:6 gives us a vision of what the prophet and God long for. The full verse is, “For I desire steadfast love (which can also be translated as mercy) and not sacrifice, the knowledge of God rather than burnt offerings.”

I mean, this is powerful stuff. This is world-changing stuff. Even though these are the words of a prophet who was centuries dead by the time of Jesus, these words are words of newness, of renewal and new life. People who have been trapped by the corruption of others, by the violence of others, can be set free, if only the people turned to true worship of God: mercy, steadfast love, and knowledge of God.

This verse is important to Jesus and he makes it a part of how he lives his life. Jesus’ life verse shaped him more than any of mine have shaped me. And maybe that’s because all the verses I memorized, and most of the Christianity I was taught growing up, were about me. The verses I was taught to hold up as important, the ones that I wrote over and over again, were about God’s plans for me, all the things that I can do, my actions, and my mind. I’ve spent so much of my life as a Christian engaging in some magical thinking, assuming that if I learned the right verses and was patient enough, God would give me the things I wanted, would open the perfect door for me to walk through on my way to my dream career, relationship, family, home. Honestly and truly, the verses that I held closest to my heart taught me things about my heart, but not much about anything else.

But not Jesus. No, Jesus’ life verse is something that opens his ministry up wide, something that transforms him, his followers, and his world. Remember, last week, we had seen Jesus travelling to the Decapolis and learning something new about the people around him: it doesn’t matter that he’s casting out demons and healing people. If he’s disrupting the status quo, he’s got to go. So he goes back to his home, and continues healing, but I think that verse from Hosea had been bouncing around in his head for a while, because instead of going to the Pharisees, going to the people in charge of maintaining the status quo, he calls Matthew. He asks a tax collector, someone who makes money off of charging people more than their fair share, to be his follower.

And Jesus keeps at it. He eats with tax collectors and sinners. He doesn’t follow the religious rules of the day. He causes a commotion by who he decides to associate with. Now, my friends, Jesus would cause a commotion in our world today too, because Jesus would not be here with us in this place. He would not be talking with upstanding citizens and people who we all look up to. He would be with the meth heads, with people living on welfare, with the unmarried mothers who have children by five different fathers, with the person who’s been sleeping in their car or a tent out in the woods. If Jesus were here in the flesh among us today, he’d have the same words for us that he has for the Pharisees, because remember, the Pharisees were good, religious people of Jesus’ day. And friends, when we lean on the verses that I learned to lean on in my youth, we will always be the good religious people that Jesus won’t have much to do with.

Because Jesus isn’t focused on the things we are so often focused on. Jesus’ life verse isn’t “plans to prosper you,” it’s “mercy, not sacrifice.” It’s not, “I can do all things,” it’s “love God with all you are and love your neighbor as yourself.” Jesus is constantly focused on what is out there, because that’s who Jesus came to this world for: the rejected, the sinners, and not the included and the righteous. Jesus can see that what has been going on already, the people who have already been reached, the ones who are already comfortable, they don’t need his attention in the immediate way that others do.

And in that, Jesus is doing something new, and is calling us to something new as well, just as the prophet Hosea called his people to new action. And new is frightening, I know, and new is uncertain and new might not succeed the first time around. We have a whole Bible full of stories of the perpetual struggle God’s people have with newness. But Jesus knows that too, and so he reminds us: don’t put new wine into old wineskins, because that will burst the wineskin and spill the wine. Make a new wineskin for the new wine.

So what does that look like for us? How do we make new wineskins in the middle of a pandemic, in the middle of such a divided time in our country, in the middle of so much difficulty? Well, through Christ who strengthens us, of course, but I think that maybe y’all and me have something in common. We have taken to heart parts of the Bible that have kept us focused on ourselves. And so before we go about making a new ministry or finding new ways to reach out or training ourselves to do new things, maybe we need to rethink the verses that we hold close to our hearts.

What was it Jesus said at the end of the Sermon on the Mount? Something about building on the solid ground his teachings and acting on them? Jesus offers us solid ground to stand on right now, when so much in the world seems like shifting sand. We just need to learn to see the world as he sees it, “orphaned and broken and staggeringly beautiful, a thing to be held and put back right.” We can do that. I’m sure that we can. We just have to find the right verses, the ones that lead to new life.

Amen.

I took two days off this week because I’m still working on the skill of planning for the Sabbath. I find that I really struggle without a routine and yet, at the same time, I’ve really struggled to get into a routine as a pastor. On the one hand, that’s a delightful part of the job: you never know exactly what each day will hold. On the other hand, that’s the overwhelming thing about the job: you never know exactly what each day will hold. Will today be the day that you engage in a soul-filling conversation about where we see love in the world or will today be the day when you find out, via an obituary emailed to you, that a member of your congregation died weeks ago and no one in the family contacted you? Will today be the day that you get to make a real connection with someone through your words or your actions or will today be the day that someone calls you to tell you that you should quit your job? There’s no way to know.

And yet, it is possible to get into a routine, a routine that feeds you and keeps you rested so that you’re ready to take on anything the day holds. I know it must be possible to get into that kind of a routine, because I’ve seen other pastors do it. But that beautiful routine of honoring a Sabbath day and keeping it holy, planning your work schedule around your rest times… I’m not there yet. And so, instead of my practice dictating my rest times, my body did instead, and I rested from writing for the past two days.

This is not to say that I didn’t think about the prompts for these three of the #30DaysofAntiRacism. I did pray about how I could speak up about injustice this week, but I believe that this writing endeavor, along with other work I’m already doing, might be all that I can manage in this moment. I have learned more about my local elections, but that has been a discipline of mine since I graduated from college. I actually enjoy doing candidate research, but this year, since I’ve been involved in local activism, I haven’t had to do as much because I’ve been interacting with local officials a lot more than I ever have before. Honestly and truly, I can’t recommend local activism enough.

Because, in the process of good local activism, you’ll find yourself caught up in a cycle of doing these three prompts over and over again. You’ll consider, and as a person of faith, you’ll pray about, what you need to do, you’ll learn the local landscape and see how your action fits within it, then you’ll engage in the action, which often involves difficult conversations. Then, once the action is complete, you’ll pray about what you need to do, you’ll learn, and you’ll do it, and the cycle begins again. I might not have a Sabbath routine, but I know this routine well. Think, prepare, do, pray, learn, act, these cycles of analysis, planning, and implementing, they’re what enable us to move forward.

And best of all, when you’re doing this world in a community, when you’re working alongside others to think, prepare, do, and think again, you have ample opportunity to mess up. You have the chance to, in the gracious community of others who want change as much as you do, stumble in any of these steps and learn from others around you. You have the chance to fall short, to apologize, repent, and make restitution, and to forge deeper relationships because you’ve done that work together. If you want to grow as a person, or at least learn about yourself, find a local cause and fight for it.

I mean, in theory, that’s what Christianity is all about. It’s about seeing the vision of the Reign of God as revealed in Jesus of Nazareth, who we call Christ, and coming together to do all that we can to live into that vision. We should always be praying, learning, and acting, and we should always be doing this in community with others who are here to pray, learn, and act with us, who are here to share their wisdom and to learn from us, here to pick us up when we fall and build deep relationships as we all struggle forward. By faithfully engaging in this cycle of praying, learning, and acting, we should be growing into the image of Christ, or at least learning the growing that we still have to do. Christianity, lived out in this joyful dance of praying, learning, acting, praying, learning, acting, praying, learning, acting, should be the work of a lifetime as we follow Christ ever more closely and love our God and our neighbors ever more deeply.

I know that so often, we make our faith and our practices this pretentious list of do’s and don’t’s, but believe me when I say that that kind of list-making is soul-killing. You will never be anti-racist enough if being anti-racist means abiding by an ever-growing list of rules that you have to follow in order to not be racist. You will never be good enough or just enough or strong enough or wise enough by creating and following rules, because goodness, justice, strength, wisdom, love, all of these things are more fluid than that. The only way to engage in these things, to grow these things, is to step into the dance.

So go. Pray. Learn. Engage. Think. Plan. Act. Learn how to dance.

(And learn that resting is a part of dancing too.)

Goodness, there’s a lot of stuff out there to read when it comes to doing anti-racist work. You can (and I recommend that you do) spend your life expanding your library to involve more BIPOC authors, but let me give you some guidelines on how to do this, which I have picked up over the course of my life.

Having fun isn’t hard when you’ve got a library card!

Listen, if you have the funds, you ABSOLUTELY should be buying books by Black authors from Black-owned bookshops. More on that in a minute. But if you don’t have the money, you aren’t left bereft. Google to find out what your local library is, go to their website, and learn their process for applying for a library card during COVID-19. Do that, then do some research to figure out what their online borrowing process is. Regardless of what they offer online, you can always download the Overdrive app. Then, you can borrow these books FOR FREE, and many of them come as audio books.

Enjoy free stuff while it lasts.

Again, if you’ve got the money, you should absolutely buy things. But if you don’t, plenty of resources are out there for free. Right now, Stamped from the Beginning is available for free on Spotify, for example. NPR’s Throughline does fantastic work to give you an overview of things and many episodes come with reading lists. Keep your eye out for resources when they come out for free, if free is something that helps you.

Buy from BIPOC-owned bookstores.

Listen, I’m not going to mess around here. Amazon is evil and should only be used as a last resort. So if you’re looking to buy books, prioritize buying them from stores owned by Black, Indigenous, and other people of color. Oprah’s got a list of 125 Black-owned stores here. If for some reason you can’t do that, at least buy from independent book stores. Or head back over to your favorite search engine and find a local bookstore and buy from them. If they don’t have a book in stock, they can order it for you.

Do you know why we do this? Why we support local book stores, independent book stores, and BIPOC-owned stores? Because money absolutely matters and it matters who we give our money to. Rich white families are doing fine. If we can spend our money elsewhere, we’re helping. Now, don’t think of this as reparations. That’s a different thing, but you can read the case for reparations here.

Buy books written and recommended by BIPOC authors.

Buy books by BIPOC authors. Buy them all. Buy children’s books, buy YA books, buy fiction books, buy fantasy books, buy non-fiction books. Buy books that tackle difficult things and books that celebrate BIPOC joy and books that just show BIPOC characters doing BIPOC things and living their lives as normal humans, because THEY ARE.

But when it comes to anti-racist resources in particular, buy from BIPOC authors. There are plenty of anti-racism resources out there. You don’t need to buy something by a white person. Yes, I hear you, White Fragility speaks to you, and there’s a lot of good reflecting that comes out of reading that book in groups. But friends, you have one precious life. Live boldly. Read books by BIPOC authors. Here’s a list of anti-racist resources from Ibram X. Kendi and here are 44 books by Black authors from Oprah magazine.

Have questions? Ask!

Well, really, ask the internet first. There is an amazing amount of knowledge out there about how to do anti-racist work. Prioritize takes from BIPOC writes, but listen, so many people have given their time and energy to educating white people. Use the information they’ve put out there for free before you ask anyone else.

Then, if you’re still lost, ask that white friend of yours who’s always posting anti-racist stuff on their social media. This might or might not help, depending on whether they walk the talk, but if they’re doing good work, they’ll be able to point you to good resources from BIPOC authors.

Whatever you do, my white friends, DON’T ASK YOUR BLACK FRIENDS FOR HELP HERE. Why not? Because they are dealing with a whole host of other things. Don’t ask them to do extra emotional labor for you in the midst of a time of racial crisis. Do the best to do the labor for yourself. I promise, once you start digging in, it’s easier than you think it is.

When you’re in learning mode, it’s okay to just listen and lurk. Follow BIPOC authors and thinkers on facebook, twitter, instagram, wherever you go to on a daily basis, and when they shout out other authors and thinkers, follow them too. Listen. Watch. Pay attention. These people are offering you a labor of love, for free, on the internet. Listen to them and follow their suggestions. You don’t need to comment, you don’t need to ask them questions, just be a sponge. Absorb. Say thank you, if you have to say anything at all.

Now. If you don’t think that you need to do all this work, if you think that you don’t have a racist bone in your body, if you think that discrimination is a part of your life, I invite you to read something different. (And even if this isn’t you, I invite you to read this work of short fiction.) It’s called The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas. You can read it for free by clicking here.

Sit with this story, please. Think about what you would do if you lived in Omelas. And if you decide that things are not okay in Omelas, go back up to the beginning of this post. Start this journey again.

A sermon for Sunday, September 6, 2020, based on Matthew 8:28-34.

Would you pray with me?

God whose love extends to places we don’t yet know, thank you for bringing us together in this time and place. By your Spirit, make your presence known here today. And may the words of my mouth and the meditations of all our hearts be acceptable to you, our Rock and our Redeemer. Amen.

You know, sometimes we don’t realize how ridiculous the stories we tell sound to people who haven’t heard them before. Our stories are our stories and most of the time, we’ve told them over and over again, so they don’t phase us anymore. Like, take for example the time that I stabbed a pitchfork right through my toe. If you grimaced, that’s the normal reaction. But I just go about my day being like, “Oh, yeah, when I was in seventh grade, I accidentally stabbed a pitchfork in my toe while we were spreading mulch as a church fundraiser. I didn’t even notice that I’d done it until I went to go walk to the car and noticed that I couldn’t move my left foot. I’ve got a cute little scar, though!”

Sometimes, we don’t recognize how bonkers our stories sound.

And I think that’s the case with our passage from Matthew this morning. Maybe you’re like me and most of your “read the bible in a year” challenges end in Matthew, so you’ve read this passage before and you just scroll on past, like, “Yeah, yeah, demoniacs, pigs, sea, I got this. NEXT!” Or maybe you’ve seen the same passages in Mark and Luke and you’re just a little numb to the details. Or maybe you know that the Resurrection is how this whole story ends and you think, “Sure, it’s cool that Jesus cast out some demons, but have you heard about how he DEFEATED DEATH??” Whatever it is, I think most of us gloss over our story today.

Which is a shame, because our story this morning has a fair amount of shock value, when we learn to read it right. So let me give you some background. As we've learned before, Matthew likes to arrange stories or teachings by theme, and this story is no exception. After Jesus finishes the Sermon on the Mount, he comes down the mountain and immediately performs several miracles and healings: cleansing a man with leprosy, healing the centurion's servant, healing many at Peter’s mother-in-law’s house, and calming the storm as he and his disciples cross the Sea of Galilee.

It’s important to notice that he crosses the Sea of Galilee. Before, when he was preaching and healing in Galilee, he was traveling through towns west of the Sea of Galilee, places like Capernaum. According to tradition, he preached the Sermon on the Mount somewhere northwest of the Sea of Galilee, though we’ll likely never know for sure. But as we read in scripture, he crosses the Sea of Galilee and ends up somewhere southeast of the Sea of Galilee, in the region of the Decapolis, or the Ten Cities. And here, he runs into a herd of pigs.

There are two important clues here, two things that tell us something about the people who live east of the Sea of Galilee.

The first in the name Decapolis. It’s Greek. And the second is in the fact that there are pigs. As some of you may know, pork isn’t kosher. In fact, pigs are unclean under Jewish law, so this tells us that the people living here aren’t Jewish. Jesus has left the neighborhood.

Now, we usually gloss over the fact that Jesus isn’t surrounded by his fellow Jewish people, because we think that everybody loves Jesus and so it shouldn’t matter who he’s hanging out with. But it mattered to the people to the people in the story. Jesus, who isn’t from around here, came into town, and the first thing he does is drive a large herd of swine into the sea. Of course they’re going to want this outsider to leave. We miss this fact when we read through this story without context. Jesus, early in his ministry, coming off of a powerful sermon and several successful healings, decides to take his message to a new region, but he gets in over his head and almost right away heads back to Galilee. We think of this exorcism as a miracle, as a good thing, but it frightens the people in the Decapolis.

But more than that context that we gloss over, we somehow just accept that Jesus DROVE THOUSANDS OF PIGS INTO THE SEA. This is the bonkers part of the story, the story that should cause us to pause. THOUSANDS OF PIGS. DROWNING IN A LAKE. And you know what? Matthew’s doesn’t even carry the whole meaning that it does when Mark tells the story. In fact, the way the whole story is told in Mark is even more remarkable than Matthew. So let’s flip over to Mark, chapter 5, one of my favorite chapters in the Bible, and read the story there.

“They came to the other side of the sea, to the country of the Gerasenes. 2 And when he had stepped out of the boat, immediately a man out of the tombs with an unclean spirit met him. 3 He lived among the tombs; and no one could restrain him any more, even with a chain; 4 for he had often been restrained with shackles and chains, but the chains he wrenched apart, and the shackles he broke in pieces; and no one had the strength to subdue him. 5 Night and day among the tombs and on the mountains he was always howling and bruising himself with stones. 6 When he saw Jesus from a distance, he ran and bowed down before him; 7 and he shouted at the top of his voice, “What have you to do with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God? I adjure you by God, do not torment me.” 8 For he had said to him, “Come out of the man, you unclean spirit!” 9 Then Jesus asked him, “What is your name?” He replied, “My name is Legion; for we are many.” 10 He begged him earnestly not to send them out of the country. 11 Now there on the hillside a great herd of swine was feeding; 12 and the unclean spirits begged him, “Send us into the swine; let us enter them.” 13 So he gave them permission. And the unclean spirits came out and entered the swine; and the herd, numbering about two thousand, rushed down the steep bank into the sea, and were drowned in the sea.

14 The swineherds ran off and told it in the city and in the country. Then people came to see what it was that had happened. 15 They came to Jesus and saw the demoniac sitting there, clothed and in his right mind, the very man who had had the legion; and they were afraid. 16 Those who had seen what had happened to the demoniac and to the swine reported it. 17 Then they began to beg Jesus to leave their neighborhood. 18 As he was getting into the boat, the man who had been possessed by demons begged him that he might be with him. 19 But Jesus refused, and said to him, “Go home to your friends, and tell them how much the Lord has done for you, and what mercy he has shown you.” 20 And he went away and began to proclaim in the Decapolis how much Jesus had done for him; and everyone was amazed.”

Different story, right? At least, there’s a lot more detail in Mark. Twenty verses verses the six we find in Matthew. But the bones of the story are still the same: Jesus crosses the Sea of Galilee, comes to a place, either Gerasa or Gadara, they’re both in the Decapolis, though Gadara is closer to the Sea of Galilee. One, or two, fierce and strong demons are possessing one, or two, men. The demons know that Jesus is the Son of God and beg to be cast into this herd of pigs nearby, the demons drive the whole herd into the water, and the swineherds go and tell everyone about it.

But the differences are important. What’s maybe the biggest difference between the story in Mark and the story in Matthew? I’d say it’s the inclusion of Legion.

We have such heart-wrenching details about the man who was possessed by Legion. He lived among the dead. He was so strong that no one could restrain him, but with all that strength, he only hurt himself. Imagine this man, the horror he must have gone through. Day and night he’s howling from the pain he’s in. No one can approach him. No one can care for him. He’s in a constant state of torture.

And how different this man is after Jesus comes to town! The people find him sitting with Jesus, clothed, and in his right mind. He begs Jesus to let him come back across the sea with him, but Jesus restores him to his community instead and throughout the Decapolis, people are amazed at what Jesus can do, all because Jesus banished the legion from him.

Not only is the story of the man possessed by Legion powerful, but the name Legion itself is powerful. Everyone in the Decapolis who heard the word legion would immediately think of the Roman legion, the thousands of Roman soldiers who were deployed to the area. The Decapolis was fully governed by Rome, part of the Roman buffer zone in the region. The whole region was possessed by a legion, so strong that no one could restrain it.

It’s no wonder, then, that the people wanted Jesus to leave after he exorcised a legion of demons and sent them into pigs. If word got around to the actual legion, to any powerful Romans, they’d see it as an act of insurrection, or at the very least, an insult to Rome. A lot has changed in the two thousand years since the Gospels, but calling the soldiers of the police state pigs is not one of them. Jesus, in Mark’s version of the story, is an outside instigator threatening the boys in red, to say nothing of the property he destroyed by sending the pigs into the sea.

So in Mark’s gospel, we have this powerful story of Jesus setting a man free, a story rich with revolutionary overtones. But we don’t have that in Matthew’s gospel. There’s no mention of Legion at all. In fact, just before this story in Matthew’s gospel, as we mentioned before, Jesus heals a centurion’s, a Roman soldier’s servant. Very different symbolism. Very different message. Instead of implying that the Roman legions should be abolished, Matthew’s gospel focuses on the fact that Roman soldiers are people too, with complex lives and people who matter to them.

So what’s happening? Why these differences in how the story is told?

Well, as we learn in biblical studies, Mark’s gospel was probably written first, in a time when Judea was in more turmoil, when it felt like maybe the uprising and instability in the area would actually topple Roman rule. The Temple in Jerusalem might not have been destroyed yet; scholars aren’t sure. But either way, there is a lot more anti-Rome sentiment in Mark’s gospel.

Matthew’s gospel, though, is written a little later, after it’s clear that Rome isn’t going anywhere. Though the gospel is still life-changing, still world-shaking, it can’t take shots at Rome like Mark’s gospel did. The community Matthew is writing for is worried about losing their lives at the hands of Rome, so we get this different version of the story, one without the revolutionary overtones. We get this story that says maybe we can live with the Roman legion.

Now, there’s an important lesson here, as we engage with both of these stories and notice how extraordinary they are in their own right. It’s easy to say that because Mark’s gospel came first, it’s a more authentic picture of Jesus, and so we should follow it. It’s equally as easy to say that the version in Matthew’s gospel is a more refined version, and so we should give that more weight. I say that it’s easy to say these things because drawing those differences in the two stories makes it easy for us to choose one over the other, depending on what we already believe. If we already believe that Jesus came to teach us how to live peaceably with the status quo, Matthew’s gospel makes that argument for us, albeit with some incidental property damage. If we believe, though, that Jesus came to set the captives and the oppressors free by radically ending oppression, Mark’s our man. No matter how much we want the Bible to comforting or challenging, the fact is that it’s both.

That’s the lesson I want us to take away from this tale of two exorcisms: both of these stories are gospel. Both Jesus the revolutionary we find in Mark and Jesus the equal-opportunity healer we find in Matthew are gospel truth, different pictures of Jesus meant to speak to different communities in different situations. One stands strong and one shows finesse. But it’s our task, anytime we come to scripture, to do the hard work of understanding all of the wisdom Jesus has to offer us and listening close to the Spirit to discern how to apply this wisdom in our lives. We have to let ourselves be surprised again by these stories, so that Jesus’ example can change us.

Because there will be times in our lives when following Jesus will be revolutionary, and there will be times in our lives where following Jesus will be a little more measured. Our task is not to immediately know what to do but to listen to the Spirit’s calling and go where we are led, trusting that no matter where the Spirit leads us, we will always be led in the way of love.

Amen.

Let’s touch on Reconstruction quickly. As a Southerner, I learned in school that Reconstruction was a truly trying time for the South. We weren’t allowed to govern ourselves, there were greedy carpetbaggers everywhere, and the economic devastation of the Civil War added insult into injury. Somehow, someway, the South struggled onward until the Gilded Age, when we shifted to learning about railroads, oil barons, and the Wizard of Oz. Or, at least, that’s my recollection from AP US History, and I’ll have you know that I got a 5 on that AP exam. I wrote a delightful essay on colonial New England, if I remember rightly.

I have to admit that, even now, I have a gap in my knowledge when it comes to the time between the Civil War and World War I. US History is hazy when there’s not a war to clarify things, but luckily, we have a memorable war at least every couple of decades (Spanish-American war notwithstanding). Still, that doesn’t help with the years between 1865 and 1914, so here’s a quick Crash Course video on Reconstruction:

Turns out that the story I remember from history isn’t exactly quite right.

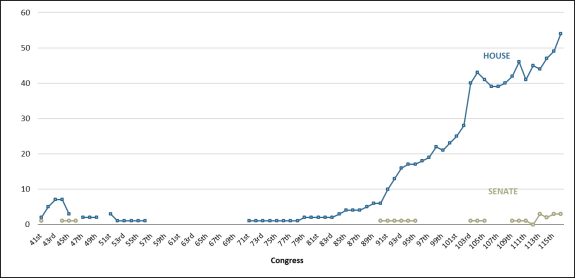

That’s okay, though, because it explains why the first Black US Senator was elected in 1870 and the first Black governor was elected in 1872, a full hundred years before I would have expected either of these things. Without Reconstruction, I would have been baffled by this graph from a report on African Americans in Congress:

For reference, the 41st Congress was gavelled in in 1869, the 57th in 1901, and the 71st in 1929. Reconstruction officially ended in 1877, after the election of 1876 was disputed and they had to come up with a compromise to get Rutherford B. Hayes in the White House.

So if Reconstruction ended in 1877, why was there still a Black man serving in Congress as late as 1901 (George Henry White of North Carolina’s 2nd congressional district, what what)? Well, Reconstruction had lasting impacts and it took a while for legislatures in the South to begin to pass the Jim Crow laws, which would eventually effectively disenfranchise the Black men who got the vote with the passage of the 15th Amendment in 1870. The Klan did its work in the late 1800s, but the Klan did have to work. Its mere existence didn’t immediately end the effects of Reconstruction. And after White left Congress, it would be 1973 before a Black person went to Congress from a state in the former Confederacy (Barbara Jordan of Texas’ 18th). And let’s be honest, in terms of holding elected office, we’re still celebrating Black firsts today.

So, what does all this have to do with GCORR’s task for today, supporting diverse leadership? Well, it’s an illustration that I hope we’ll apply to our churches, our schools, our organizations, and our workplaces in addition to those we elect to office. If we call for diverse leadership at any level, we white people had better be will to back up every single BIPOC leader who is put in place, because there will be backlash to it, even today. White supremacy is everywhere, as we’ve discussed before, and each attempt to dismantle it, however small, has consequences.

Think about Reconstruction. White Southerners hated it, clearly. They hated it enough that they were willing to rewrite the history of the era while they transformed the history of the next through violence and voter suppression. But white northerners got tired of it too. It was too much work to continue to fight for the rights of Black folk in the South and without radical pressure pushing to keep Black people in office where they can make decisions on behalf of their people, white people used every tool in the book to vote them out and keep them out for seventy years.

Of course we should call for racial equity among our leaders. I don’t want to discourage that. But I do want us to be aware of what we’re asking those BIPOC leaders to be and to do and to support them while they do their work. As the third pastor who is a woman at one of my churches, I still feel push back against my leadership, and we’ve been ordaining women since 1968. Can you imagine how much harder it would be to be a Black person leading white people in any capacity?

Anyway, here are the voter guides from the NAACP: https://naacp.org/resources/state-voter-guides/

Once, while out supporting the protests in my community, a gentleman came up to us to ask what we were protesting and why. I watched as the person he approached first, a passionate high school student, explained the history of the monument and why we believe it should be moved, paying attention to his body language as they talked. When the man who approached us started waving his arms around, I walked over to see if I could help calm the situation down. We ended up having a good conversation, except for when I brought up white supremacy and he said, “White supremacy? Where? Give me one example of white supremacy today.”

I have to admit, I was flabbergasted.

Because once you know to look for it, white supremacy is EVERYWHERE. Again, I don’t mean people in white hoods parading down our streets. I mean something a lot more pernicious and enduring than those blatant public displays, though of course things like that do still happen. No, I mean all of the foundational ways in which white supremacy is baked into nearly everything we do in this country. If you’re a book reader or listener, Stamped From the Beginning is free on Spotify right now and Kendi will walk you through the origin of white supremacy and racist thought, how it has morphed over the centuries, and how we experience it today. Or read or listen to An Indigenous People’s History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, for how the white European colonialist mindset has wreaked havoc on Indigenous peoples, and still does to this day. And believe me, once you know to look for it, it’s there.

By white supremacy, of course, I mean the very basic idea that white people are the best people. Now, I know that sounds ridiculous and childish and, because it’s childish, not nefarious at all, but white supremacy is one of the most powerful forces in the United States. White supremacy is what justified the slaughter and genocide of the Indigenous population of the land that would become the United States. White supremacy is what justified the slave trade and the life-long and cross-generational enslavement of Africans. White supremacy is the battle that must be fought even after the treaties are signed and the slave chains are broken, because white supremacy insists that white people are smarter, more talented, and more cultured, inherently, than people of any other color. White supremacy says that Black and Brown people are just lazy and that’s why they don’t make enough money to pay for food for their families. White supremacy says if they just looked and acted more like white people, if they just worked a little harder, these people would be more than capable of providing for their families.

Of course, white supremacy has also stripped people of generational wealth (see: genocide and mass enslavement above), dismantled thriving Black communities when they did build wealth for themselves (see: the Tulsa massacre and the building of the Durham freeway, among others), concentrated wealth among white people (see: the GI Bill and redlining), and still to this day makes it harder for BIPOCs to get an education, to be hired at jobs, and to work at those jobs. This is, of course, to say nothing of mass incarceration, which I bet we’ll get to in another post this month.

This, my white friends, is what I need you to understand, as we ask you to donate or volunteer at food banks and pantries that serve BIPOCs. These people don’t need your pity or your white guilt. They don’t need you to look down on them for their lot in life. While in this particular moment, yes, they might need help getting food on the table, what they also need is for us white people to realize that the system is rigged against them. Always has been. It was designed that way. Genocide and perpetual enslavement are such grave sins that we had to reorder the world in order to justify them and that reordering doesn’t just undo itself. We have to do that, and we have to do it faster than we’ve been, because it is starving our siblings. It is killing them in the streets. If we don’t help them in their fight to dismantle the systems our ancestors put in place, we have their blood on our hands too.

Anyway, in the meantime, help us feed people.

You can donate to the food pantry at my church by clicking here and giving to Whittier United Methodist Church in Whittier, NC, part of the Smoky Mountain District, with me, Jo Schonewolf, serving as pastor. Make sure to put “Grace House Food Pantry” in the description. We serve anyone who comes and though the majority of the people are white, we have a fair number of Indigenous people (mostly Cherokee) and Latino people who we serve, along with a few multiracial families. You can also give to MANNA, a part of Feeding America, who gives food around the Asheville area, including my communities. Or, if you’re around Sylva, you can help Reconcile Sylva collect non-perishable goods for our food drive between now and September 18th. Contact me for details!

So, a funny thing about today’s prompt from GCORR: intercultural and anti-racist are not the same thing. They may overlap, for sure, but when engaging in anti-racist work in the United States, you should be first and foremost concerned about anti-racism.

This is not a world-ending critique, of course, just a call for us to intentionally choose what we’re focusing on. This moment in the United States is, first and foremost, focused on confronting personal and systemic anti-Black racism, wherever it may be found. If we’re doing good intersectional work, the benefits of our work will reach beyond anti-Black racism, but to call people to intercultural work is a different thing entirely. Reading a book by a white Canadian or French or English author is intercultural work, but it’s not anti-racist work and honestly, my fellow white people, what we need right now is to do anti-racist work.

I’ve also felt very, very convicted by a tweet I saw months ago which said something to the effect of, “Black people are asking for change and white people join a book club.” This is not to say that education isn’t important, of course. This is not to say that white people shouldn’t read a book before asking a BIPOC friend of theirs questions about race. But we need to meet the moment we’re in, and as much as that moment has shifted since May, the moment still asks for us to put more than just our reading list on the table.

So, follow GCORR’s suggestion today if you’re just now dipping your feet into the waters of anti=racist work. It’s not a bad suggestion. Just don’t let yourself off the hook. Reading The Help or Love in the Time of Cholera isn’t doing anti-racist work. Jump into a reading group that’s going to tackle something a little more weighty.

In fact, if people are interested, I would love to re-read Beloved by Toni Morrison as the weather, hopefully, turns colder. You can surely grab a used copy somewhere. But don’t let GCORR’s suggestion today send you into a land of white comfort where we all read White Fragility and reflect on how fragile we indeed are, while surrounded with the metaphorical bubble wrap of other white people. Push yourself to dig into something deeper.

Or, you know, take this opportunity to evaluate your friend group. If your friends all look pretty much like you, think about why that is. Because it is possible for “intercultural” conversations to be a part of your everyday life, and not in a soul-crushing way. Today, me and a friend of mine navigated together the sometime fraught waters of finding a tattoo parlor with a tolerable level of racism. Tonight, my partner and I will continue to talk about the racial dynamics in academia, because that’s a primary concern in his career. Now, hear me: I’m not telling you to go out and get a Black friend or a Latinx partner. I’m not saying I’m a better person because I have friends with different amounts of melanin than I do. Each and every friend I have who isn’t white can tell you that I still stumble, despite my commitment to doing anti-racist work. But your relationships are worth thinking about, and I encourage you to think about them.

In the meantime, I have two conversation-based pieces of content for you to interact with, in case you haven’t found your group today. The first is Uncomfortable Conversations with a Black Man.

And the second is Conversations with People who Hate Me:

Check out the podcast wherever you listen to podcasts, or by going here.

Before I start, let me invite you to think about your own racial autobiography. The GCORR has this checklist to get you thinking, but I’d also recommend reading through Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack if you haven’t before, or watching Peggy McIntosh’s TED talk, if that’s more your speed. Do both, though. It can be really, really helpful to realize the amount of diversity you’ve been exposed to over the course of your life and, if you’re white, to recognize how your privilege plays into that.

To the surprise of everyone I talk to, I’m from Caldwell County, North Carolina. People are surprised because they don’t think I have enough of an accent to come from furniture country deep in the foothills, but believe me, I know how to pronounce Appalachian and I have just as much of an aversion to final g’s when I speak as the rest of us do. But being from the particular end of Caldwell County that I’m from, growing up in the 90’s and 00’s, I didn’t have much experience with people of other races until I went to college.

This isn’t to say that I only knew white people. In sixth grade, when we were practicing filling out the student information section on our End of Grade tests, I remember balking at the idea that anyone in my class would have to fill in a bubble other than Caucasian. I insisted that my two Asian classmates were white. I can’t for the life of me remember what my teacher said in response, but honestly, sixth grade was the first time I realized that not everyone in the world was white. I had traveled around the Sun twelve times before I understood that race was a thing.

Now, again, this was the early 2000s. We were very big on being colorblind back then, very insistent that if we just declared everyone equal, they would be. I mean, we had achieved MLK’s dream, hadn’t we? And I kept that viewpoint for most of my middle school, high school, and, let’s be honest, college years. The two Black people in my graduating class were brothers, but sandwiched in between them during graduation was my so-white-she-gets-freckles-in-the-sun friend, Jessie. We laughed about it. We didn’t talk about how all the Hispanic kids hung out together or how we had a “redneck hall” that was exactly as white as you expected it to be. I lived in a meritocratic world, so to me, for much of my early life, talent was what mattered. Race was just a secondary characteristic, as far as I was concerned.

But it was a whole other world at Carolina. Suddenly, I had Black and Brown friends from band or from class. My core friendships were still white, but I had a Jewish friend and I had Black friends that I could say hello to when we walked past each other on the quad, so I felt very, very worldly by the end of my first year.

Actually, let’s back up. I need to talk about Camp Joy.

Camp Joy was a non-denominational (so, Southern Baptist) Christian overnight camp that I worked at for eight weeks each summer, starting the summer after freshman year of high school. The camp director, after my first summer, was Black, and his mixed race family worked on camp staff, which was great, because we had a diverse group of kids who came to camp each week. For many campers, camp was free, or at a reduced rate, because a plurality if not a majority of the campers were recommended to the camp through DSS. I will forever and always be so deeply torn about my experience with Camp Joy.

On the one hand, these summers have been a perpetual blessing in my life. I keep up with former campers and with fellow camp counselors on facebook and I am often so, so proud of the people we have become. My leadership skills, my gifts and graces for ministry, all of these things were first truly recognized at this camp. And while I remained oblivious to the racial dynamics at play at camp, I learned a bit about Black culture during my time at Camp Joy and I truly and deeply value the way my world expanded while I was at camp. On the other hand, the Purity Movement was EVERYWHERE at camp. I learned that the only thing I ever had to be ashamed about [as a white girl] was my body and the way it caused boys and men to sin, and that is a difficult thing to unlearn.

So at Carolina, I went from summer camp friendships with mostly lower class Black and Brown people to friendships with Black and Brown people who were smart enough and lucky enough to make it into UNC. My experience with Black culture shifted. Instead of being stubbornly who they were, which is how most of my campers and fellow counselors experienced their Blackness, most of my Black friends in college would code switch. (If that’s a new term for you, NPR has a podcast by the same name for you to binge.) Again, I fell into that myth of meritocracy. We’re all the same if we’re at the same ability level now. Your background doesn’t impact who you are. All that matters is what you’re doing now.

It was 2011 before the bubble of this worldview burst for me. I was working at another summer camp, this time at the planetarium, and one of my fellow camp staff pulled me aside. We had been trading off dealing with a kindergarten camper who needed a little more attention than most, due to his tendency to get a little bitey with other campers, and I had followed her lead in talking to him. “Now, Mr. Paige,” I said, sitting down with him just as she had done. “I know I’m not talkin’ to you again about how we can’t be bitin’ our friends, right?” After a few minutes minutes of talking and a few more minutes of quiet time away from the group, I sent him back to his room and we went on with the rest of our day, answering calls on the walkies and floating from camp session to camp session.

Now, I hadn’t thought twice about what I did, with my coworker sitting behind the main camp desk and listening the whole time. In fact, I felt a little bit of pride, having picked up a new, effective disciplinary style. There was no more biting for the rest of the day. But, as my coworker explained to me after the pickup line had ebbed down to a trickle, the problem was that my fellow camp staffer was Black and I had mimicked her method, right down to the accent and mannerisms. It was cultural appropriation at best, but really, it was mocking. It took me years to pick apart why, but this, really, was the first time that I was called out on something racist that I’d done, simply because I didn’t think that race mattered.

Now, I spent years in that uncomfortable space, realizing that race does, in fact matter, and that claiming that you don’t see race is actually just something that white people get to do that has no real impact on the world, without really know what to do with this information. I started to learn that you didn’t have to put on a Klan hood in order to do something racist and that I had implicit biases. All of this was happening on a personal level as we re-elected our first Black president and as the Black Lives Matter movement began on a national level, and it was also happening when something very particular was taking over the internet: tumblr.

I found tumblr because of Welcome to Night Vale, and that was particularly fortuitous, because if it had been through the Harry Potter or Supernatural fandoms, I would have seen more slash fics and less POC/LGBTQIA educational posts. I learned that I need to diversify my timelines and the other media I consumed. I learned the word woke (ah, 2014) and I learned that there were so. many. ways. to discriminate against others, even without intending to. I did a ton of informal learning just by listening to people on the internet who had different life experiences from me, especially different racial experiences.

My more formal education about race came during seminary, when I went to Wesley in Washington, DC, in the fall of 2016. I mean, I knew enough about racial dynamics to recommend that my Science and Religion program at Edinburgh incorporate more thinkers of color (because BOY, if you want to see a bunch of white men talk about philosophy and religion, you can’t do much better than studying Science and Religion as a field—and I thought physics was bad!), but outside of that, I had no real tools for learning going further in my learning.

At Wesley, though, I had more Black classmates and professors than I had ever had in my life. I’ll never forget having Dr. Beverly Mitchell for my introduction to philosophy for theology class, a class I resented having to take since I had already taken Philosophy of Time and thought that that should count. Dr. Mitchell taught me about questioning the philosophy that I took for granted, how to read theologians generously but not without critique, and how to notice all of the ideas at play. Anti-racist work was woven throughout each of these lessons. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

I learned from my classmates, really listening to their experiences for the first time. I read and read and read so many thinkers who were not white, who didn’t have anything like my background. I absorbed all of this information, feeling like a sponge, not knowing that it was actually a lifeline. Engaging with Black and Brown people’s words, thoughts, sermons, music, art of all kinds, experiences, all of it kept me human. I learned so much about being like Jesus just by being around people who were not like me. I learned, too, to see how so many of the systems that have shepherded me through my life, including the church, were built with racism in mind. What had been a self-righteous awareness that race existed grew into a complex understanding that the past and present of race and racism in this country alone was an immense thing to grapple with, but grapple with it I must. I’m glad to be past seminary in many ways, but I’m so grateful for this astounding work of learning and reshaping God did within me during these years, years when it would have been so easy to disengage from the hurts of others and retreat to places of quiet, white comfort.

In the year and couple months since seminary, I’ve continued to grow, continued to hone my understanding of racism in this world. I’ve struggled with how to teach others, how to share this life-giving information with others. I’ve felt myself called over and over again to compassion for Black, Indigenous, and other people of color, called to guide others on the journey from comfortable white colorblindness to something more like the truth. I long for a world where we can celebrate the joy that comes from glorious diversity that humanity contains, and though the dominance of white supremacy dampens that joy, it’s never completely gone. The Maker of All Things made us to be different from one another not so that we would forever be in conflict, but so that we might learn to recognize holiness outside of ourselves. There is holiness bursting through everywhere in this world and where there is holiness, there is joy. I hold out hope that we’ll all be able to see it and live into it one day.

I invite y’all to think through your own racial autobiography. There’s so much that I’ve left out here: Black authors that have changed my life, the march in DC where the pain, strength, and hope of Indigenous people crept into my heart and made a home, friends who have been patient with me and struggled with me, my trip to South Africa, settling into my Appalachian heritage while also learning that my experience is such a narrow slice of it. I’m sure your stories are just as complex, but sit down and start thinking about what your story is anyway. Reflection, in the right amount, is good for the soul.

I can remember being in elementary school and showing one of my friends a story I was working on. It was probably about a princess who could both rule and fight, because I watched Star Wars a lot when I was little and my takeaway was that if you can be anything in this life, be Princess Leia. Or maybe it was a ghost story. I really loved the idea of ghosts righting wrongs in the world after this one, and I’m an October baby. Spooky is in my stars. But whatever it was, what I remember most from showing this story to my friend was her saying, “You wrote this?”

I remember the same reaction from some of the other counselors at the Christian summer camp I worked at when I showed them another piece of writing of mine. I can’t think of what it was, exactly, but I remember them pouring over it as a group, binder laid open on the meeting room table, and that same question of surprise coming from them. “You wrote this?”

This is not to say that my writing has always been superb or praiseworthy. I did, after all, get a 2.5 on the North Carolina Writing Test in 4th grade, the lowest scored you can get and still pass. The prompt told us to describe our favorite birthday and if I, a little white girl whose father still had a full time job with benefits, struggled to describe my favorite birthday, I can only imagine the fictions some of my classmates had to invent. I got points taken off because I kept repeating, “It was great,” but, like, we had a party at a putt putt course, which is now a Wendy’s and a gas station, and I got to be the director of my own Samantha the American Girl Doll play, which, in general, was great. I don’t know what else they wanted from me. It was a dull prompt.

I’ve also found my urge to write quashed over the past few years as I’ve come to terms with the church, the Purity Movement, and the spiritual harm it caused. No amount of surprised delight at my writing could lift me out of those depths.

See, I used to keep dense prayer journals, ones I’d write in daily with all my thoughts and hopes and dreams, my deep confessions and my honest questions. This was my primary spiritual discipline, the main way I connected with God. I would write and write until my hand cramped, memorizing the names on my prayer lists as I wrote out prayers for them daily. So much of my spiritual growth was done in these prayer journals, and I kept the practice up all the way from high school into my sophomore year of college.

Then, it was blogging. I wrote out all of my college angst about what to be and how to go be it. My fiction wasn’t ever very good, though I did NaNoWriMo year after year, but my blog posts, essentially stream-of-conscious essays focused around a singular topic, got a fair amount of approval when I shared them on facebook. I kept the blog up for years, shifting spaces here and there, and by the end, I had a few hundred people reading what I wrote. I held out a secret love for my writing and secret hopes that the right person would read it and launch my writing career. I wasn’t sure what genre I’d write in, specifically, but since most of the affirmation I received was from church people, I assumed that God had given me a gift and that, if I just continued to use this gift, good things would come of it.

As I entered grad school, though, my classwork took up most of the mental energy I had, along with some depression and anxiety. On top of that, I found myself in a new church setting, something different than any church I had been in before. There wasn’t a choir for me to sing in or an instrumental ensemble for me to play in. My efforts to get involved in the ministries I was used to participating in were largely ignored. And the church had split from the Church of Scotland over gay marriage. One of the first sermons I heard was about the nature of biblical marriage and God’s grand plan of fruitfulness in marriage.

I am truly thankful for those of you who are unfamiliar with those evangelical buzzwords. I’ll explain it all another time, but suffice it to say, I had, for the first time in my life, found myself in a church environment that was openly opposed to what I believed. Not just, “Oh, Carl didn’t nail the sermon this week,” but “Holy hell, I can’t believe this man is saying this.”

I don’t mean to paint a picture that I had never doubted or questioned my faith before. I had done a fair amount of tearing things apart and putting them back together as a physics and astronomy major and then informal science educator working in the Bible Belt. But I had always felt like church was home and that no matter how much I was wrestling with God, I would be surrounded by people who loved and cared for me, people who welcomed me and supported me. It was clear to me that this church wasn’t that.

Now, the cracks in my trust in the church had been there before I started going to this church, and this church wasn’t the one to break me wide open, but I know that the ground started to shake underneath me during the year I attended there. And it’s hard to put pen to paper as the ground shakes underneath you.

The full story of my unraveling soul is perhaps one for another time, but suffice to say, once I got out of the habit of writing, I couldn’t convince myself that I was good enough to come back, not routinely. As I finished one masters and started working on another, I also start digging into the painful places in my heart, places where evangelicalism and the Purity Movement had cut into me and left my wounds to fester. When your sense of worthiness is tied to your sense of physical purity, which is tied to your relationship with God, to which you have tied your ability to write, well, your blog gets a little dusty.

With the help of therapy and some antidepressants, though, I feel like I’m putting myself back together, better than I was before. I hope, and sometimes pray, that this is solid foundation I’ve been longing for. I’m tired all the way down to my bones from all this instability. And as I put myself back together, I’ve found myself dream of little stories once again, planning posts in my head, and aching for the keyboard under my fingers. I hope it’s time to start again.

So, in a fashion that you, dear reader, will come to know is distinctly mine, I’ve decided to jump back into the swing of things by committing to writing a post each day, no matter how long or short, for the month of September, following the United Methodist Church’s General Commission on Religion and Race’s 30 Days of Anti-Racism calendar. I’ve been doing a fair amount of anti-racist work in these past few months, but I know in my heart that I need to set aside time to reflect on it too. It’s just a part of being white in these days: listening, learning, doing, reflecting, all in a perpetual loop. This loop is important for most things in our lives, but in this time of increasing racial consciousness, it’s especially important now.

So count this for September 1, no matter how late it’s published. I’ve committed to prayer and I’ve committed to action, and we’ll go from there.

How about y’all? How do you feel God is calling to you in this time? What anti-racist work lies ahead of you? Has the church been holding you back or propelling you forward?

A sermon for Sunday, August 30, 2020

Would you pray with me?

God whose love reaches out to both the foolish and the wise, thank you for bringing us to this time and this place. By your Spirit, make your presence known among us here and now. And may the words of my mouth and the meditations of all our hearts be acceptable to you, our Rock and our Redeemer. Amen.